In Cox’s Bazar, community volunteers known as Elephant Response Teams (ERTs) are on the front lines protecting Bangladesh’s remaining wild elephants from a dire extinction threat. These grassroots efforts are a crucial part of a larger conservation strategy focused on minimizing human-elephant conflict, which has been exacerbated by habitat loss and the influx of Rohingya refugees in the region.

The Vanishing Giants

The Bangladeshi species is Asian Elephant, the flagship species of most of the tropical forests of Bangladesh. According to the surveys carried out by IUCN during 2013-2016, three types of elephants are found in Bangladesh. They are resident, migratory and captive.

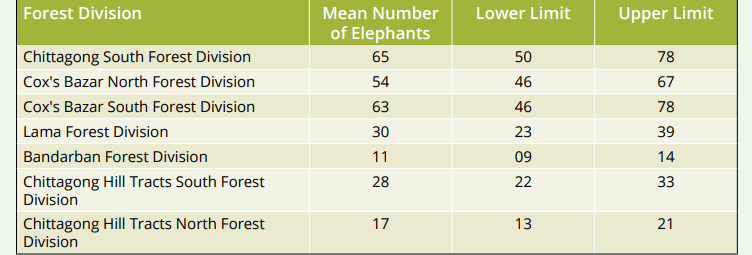

- Wild residents: Approximately 268 Asian elephants are thought to reside in Bangladesh.

- Migratory: Around 93 elephants seasonally cross into Bangladesh from neighboring India and Myanmar, primarily for food.

- Captive: About 96 elephants are kept in captivity for various purposes, including logging, circuses, and safari parks. In 2024, the High Court suspended licenses for captive rearing to protect them from exploitation.

In the Southeastern regions, the Chittagong Hill Tracts and Cox’s Bazar forest divisions are a stronghold for resident wild elephants. The Northeastern region is mainly used by migratory herds traveling from India. These elephants often come into conflict with human settlements.

Bangladesh’s rapid population growth has driven large-scale deforestation and habitat loss, forcing the giant wilds into human settlements in search of food and water. Expanding settlements and land grabbing have destroyed key elephant corridors, especially after the construction of Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar. Unplanned infrastructure projects, including the Dohazari–Cox’s Bazar railway, have further disrupted migration routes, with illegal electric fences causing fatal electrocutions.

As elephants raid crops, escalating human-elephant conflicts have led to casualties on both sides. The number is 34 elephant deaths recorded in 2021 alone. Though less common, poaching and wildlife trafficking continue to threaten elephant populations in border regions.

Locals Take the Lead to Protect Elephants

In Bangladesh, local villagers and youth groups organize community-based Elephant Response Teams (ERTs) to mitigate human-elephant conflict. Supported by the Forest Department and organizations like the IUCN, these teams use patrols, early warning systems, and awareness campaigns to safely deter elephants, protect crops, and conserve the endangered species.

The ERTs are composed of trained locals who act as the first line of defense against elephants entering populated areas. A shout from a patroller or watchtower is often the first sign of an approaching elephant herd, triggering a rapid community response.

Villagers are encouraged to plant crops that elephants dislike, such as chili, taro, and bitter gourd, around their fields. Training and subsidies are sometimes provided to help farmers adopt these non-preferred crops to minimize raids.

Threats to Elephants in Cox’s Bazar

The Asian elephant population in Bangladesh is critically endangered and faces severe threats from human activity.

Construction of Rohingya refugee camps since 2017 has led to the clearing of thousands of acres of forest in Cox’s Bazar, which is prime elephant habitat. Large-scale infrastructure projects, such as railway lines, highways, and border fences, have cut off ancient elephant migration corridors, trapping herds in smaller, fragmented areas.

As elephants search for food and safe passage, they are forced into human settlements and agricultural land, leading to fatal encounters. The conflict has been exacerbated by the increased human presence in elephant corridors.

A Growing Concern

Human-elephant conflict is a growing concern in Bangladesh. Habitat loss, fragmentation, and a shrinking food supply for elephants forces them into human-inhabited areas. As a result, elephants raid homesteads and crop fields, causing significant economic losses for local communities. The conflict has led to injuries and deaths for both humans and elephants. Villages surrounding elephant habitats are at a higher risk of attacks, especially those with fewer resources.

According to the Bangladesh Forest Department, there were 268 resident elephants in Bangladesh in 2016, residing in its southeastern forests. Meanwhile, during the period of 2017-21, at least 50 elephants were killed in human-elephant conflicts and electrification by humans. Of them, 34 were killed in 2021 alone.

Innovative Approaches to Coexistence

Considering the recent rise in elephant killings, the Forest Department has planned a new conservation project to save the endangered species by minimizing elephant-human conflicts and reviving their habitats.

Under the new elephant conservation project, orchards growing plants that elephants prefer to eat, such as calamus palms and bamboo gardens, would be introduced to ensure their safe habitat, breeding and food security.

Organizations like the IUCN and the Bangladesh Forest Department have established ERTs composed of local volunteers in conflict-prone areas of Cox’s Bazar.

- Volunteers patrol areas to monitor elephant movements.

- They use tools like watchtowers, flashlights, and loud noise to warn communities of approaching elephants and guide herds away from human areas.

- They also raise public awareness about elephant conservation and ways to mitigate conflict.

Newer systems use seismic sensors or cameras with deep learning to detect elephant movements and alert response teams.

Bangladesh Railways is installing an elephant warning system along new tracks in elephant habitats. This system uses seismic sensors to detect vibrations caused by elephants and alerts train operators to prevent collisions. Simple, low-tech trip-alarm systems have also been implemented to alert households when an elephant crosses a designated perimeter.

The story of Cox’s Bazar shows that real conservation doesn’t always start in boardrooms or policy papers. It begins in villages, with people who care. If Bangladesh can strengthen and scale these grassroots efforts, the path to coexistence could become the country’s greatest environmental success story.

For more such informative articles stay tuned at The World Times.