As films, books, stand-up, and even tweets face growing restrictions, India confronts a deeper question: What remains of democracy when only selective voices are heard? Is the growing Censorship harming Democracy?

Screen writer and actor Murali Gopy recently posted a pointed quote by American literary critic Henry Louis Gates Jr. :

Censorship is to art as lynching is to justice.

While he didn’t name the film explicitly, the remark appeared to refer to the controversy surrounding ‘Janaki vs State of Kerala’, a film starring Suresh Gopi.

The Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) denied certification to the film over the protagonist’s name—Janaki, another name for the goddess Sita.

The board argued that portraying a sexual assault survivor with that name could “hurt religious sentiments.”

Producers, prioritizing the release, agreed to changes. The film’s title was revised to “V. Janaki vs State of Kerala”, and all spoken references to “Janaki” were muted.

This isn’t the first time Murali Gopy has faced censorship. His earlier film Empuraan, directed by Prithviraj Sukumaran, was also asked to remove scenes allegedly linked to the 2002 Gujarat riots.

When Censorship Becomes Policy

Another case of bureaucratic opacity came when the Bengali film Kalponik, screened at the Kolkata International Film Festival, was delayed by the CBFC.

The director claims that the board refused to provide written reasons for withholding certification. CBFC officials, however, maintain that all protocols were followed.

Praised By the World, Obscured at Home

In 2024, Santosh, directed by Sandhya Suri, was announced as the UK’s official Oscar entry. But in India, its release has been indefinitely delayed.

In March 2025, the CBFC blocked the film entirely, citing its depiction of ‘Islamophobia, Casteism, Misogyny, and Police Brutality’. Indian censors demanded cuts to tone down any potentially “offensive” content.

Speaking to The Guardian, Suri said she was “surprised,” noting that Santosh didn’t introduce anything new or unexplored to the Indian Cinema scene.

When Laughter becomes Risky

Censorship has also crept into India’s stand-up scene. Not long ago, Comedian Kunal Kamra faced backlash for jokes about Maharashtra Deputy CM Eknath Shinde.

The aftermath included alleged violence at Habitat Comedy Club, copyright takedowns on YouTube, and online harassment.

Still, Kamra refused to back down, questioning whether censorship is now being weaponized to silence dissent.

Similarly, an episode of India’s Got Latent, aired on February 9, sparked disproportionate outrage, police complaints, and even death threats over remarks perceived as offensive.

Censorship Beyond the Stage and Screen

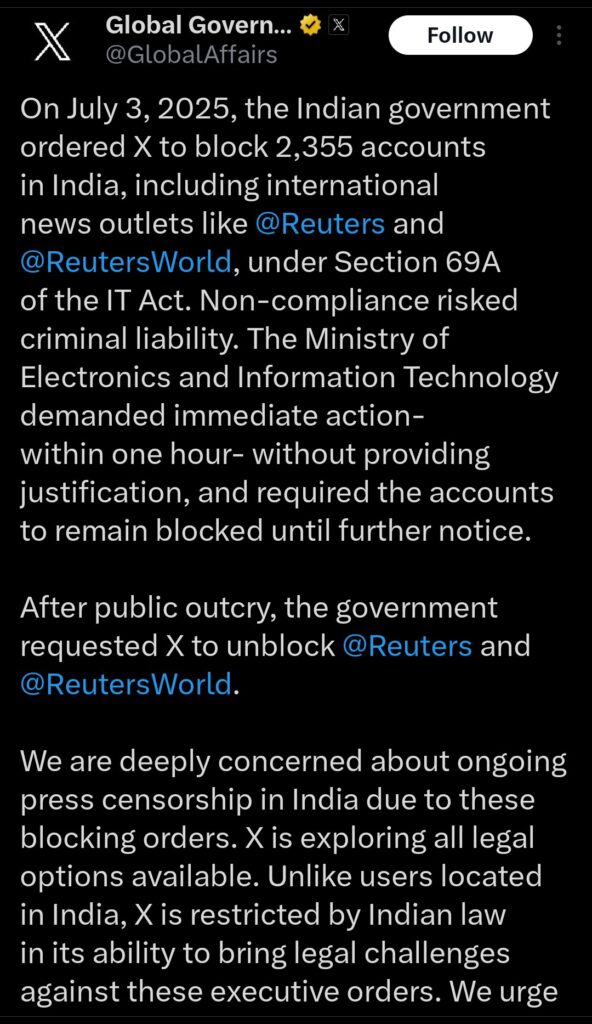

It is not just creators facing suppression. On July 3, 2025, social media platform X (formerly Twitter) disclosed that the Indian government had ordered the blocking of over 2,000 accounts, including those of Reuters and Reuters World, under Section 69A of the IT Act.

In a public statement, X announced on the platform:

“We are deeply concerned about ongoing press censorship in India due to these blocking orders.”

The accounts were reportedly restored within an hour. The Indian government later denied issuing any such order, stating there was “no intention to block any prominent international news outlet.”

Censorship: A Slippery Slope

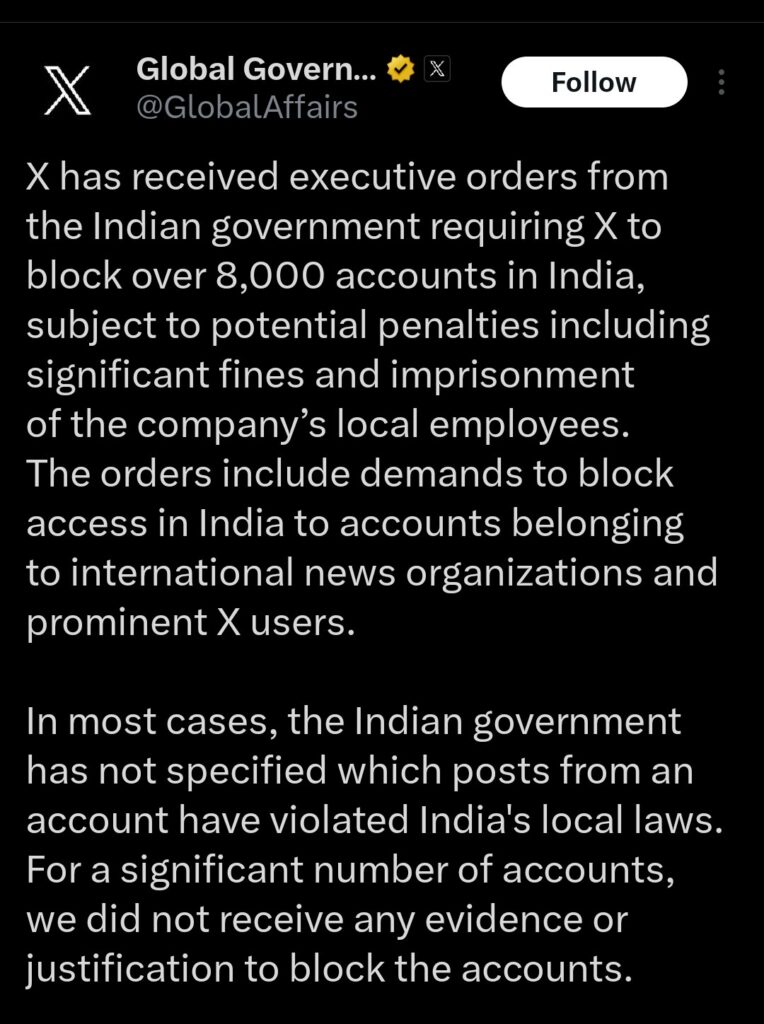

This incident followed an April 2025 order, blocking over a dozen Pakistani YouTube channels after a terror attack in Kashmir, citing the spread of “provocative” content. Amidst Indo-Pak tensions, on May 9, 2025, the Indian government ordered X (Twitter) to withhold 8,000 accounts from India.

Several independent outlets, including The Wire, BBC Urdu, Maktoob Media, The Kashmiriyat, and Free Press Kashmir, reported restricted access.

Shaheen Abdullah, the deputy editor of the Maktoob Media, told Frontline:

“The ban blatantly violates the law of the land and the whole idea of free media. It is an attempt to muzzle and choke independent media outlets. Moreover, it is a sign how press freedom is deteriorating in India.”

Where do we go from here?

Censorship in India is not new. But its expanding scope, increasing opacity, and use as a tool of political convenience raise urgent concerns.

Why do certain films receive state promotion, tax incentives, and institutional support, while others face bans merely for addressing sensitive issues such as Dalit Oppression, Communal Tensions, or Patriarchy?

When art and opinion are filtered through ideology, what remains of democracy? What determines which stories are considered too dangerous to tell?

Across film, comedy, journalism, and social media, a pattern seems to be emerging: content that challenges dominant or majoritarian ideologies faces disproportionate scrutiny, gets banned or quietly disappears.

Whether this climate will lead creators to self-censor or inspire them to resist remains to be seen.

Does the Majority agree?

We cannot reduce a population as vast and diverse as India’s to a simple yes or no. It is also difficult to determine whether people are aware of the increasing censorship or whether they fully understand its implications. With self-censorship creeping into the press, the news we receive often follows a single unspoken motto: Don’t offend.

All we can do is keep asking questions and wonder—

Is India inching toward an Orwellian 1984-esque reality?

Let us know your thoughts. For more such news, Stay tuned at The World Times.