Indian health authorities have confirmed a Nipah virus outbreak in West Bengal. Officials, however, say the situation is contained, with only two confirmed cases to date. The Union Health Ministry reported that both patients were identified in December 2025. The reported cases triggered an extensive public health response aimed at preventing further spread.

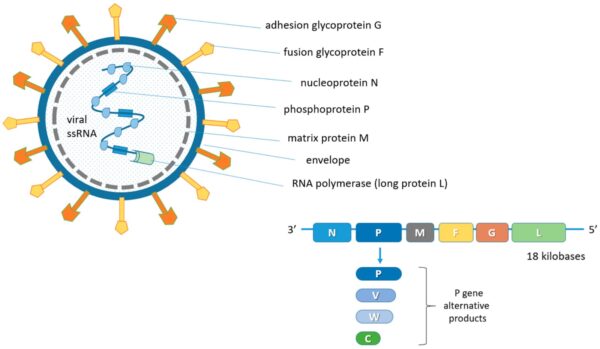

The Nipah virus (NiV) is a highly lethal zoonotic virus, meaning it spreads from animals to humans. The virus has triggered heightened health monitoring domestically and across Asia. Though limited in scale, the outbreak has drawn regional precautionary measures, including airport screening in several countries, to protect travellers.

Current Situation and Government Response

Contrary to some alarming social media claims, verified government data shows the outbreak remains small. Authorities have confirmed only two cases in West Bengal, both linked to healthcare workers. Health authorities traced 196 close contacts, all of whom tested negative and remain symptom-free, according to official statements.

India’s Health Ministry said it “ensured timely containment” by quickly deploying surveillance teams. Alongside this, authorities are enhancing laboratory testing and undertaking field investigations to isolate and monitor contacts. The agency emphasised that the incorrect figures circulating in the media have been speculative.

The National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) and state agencies worked with hospital networks to manage the response, isolating suspected cases early and imposing quarantine measures where needed.

Regional and International Precautions

Although no spread beyond West Bengal has been confirmed, several Asian countries have reinstated health screenings at international airports following reports of the outbreak. Thailand, Taiwan, Nepal and others have introduced temperature checks, health declaration forms and visual symptom monitoring for passengers arriving from India.

Public health officials stress that these measures are precautionary and not indicative of widespread Nipah transmission. Authorities have modelled these measures on COVID-19-era screening strategies, tailoring them to the known transmission patterns of the Nipah virus.

What Is the Nipah Virus and Why It Matters

First identified in Malaysia in 1998, the Nipah virus takes its name from a village where the virus was first detected among pig farmers and has since emerged periodically across South and Southeast Asia.

Fruit bats, particularly flying foxes, are the natural reservoir of the virus. Humans can become infected through direct contact with infected animals, consumption of food contaminated by bat saliva or urine (such as raw date palm sap), and close person-to-person contact once symptoms develop.

Symptoms begin with fever, headache and respiratory issues but can rapidly progress to encephalitis (brain inflammation), seizures and other complications, which can be fatal. The incubation period typically ranges from 4 to 14 days, though longer durations have been reported.

The fatality rate for Nipah virus infection is high, between 40–75%, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), making it far more deadly than many seasonal infections.

Treatment, Prevention and Expert Views

There is no licensed vaccine or specific antiviral treatment for the Nipah virus. Current clinical management focuses on supportive care, including hydration, treatment of complications and intensive monitoring in hospital settings.

Experts point out that because there is no effective drug treatment yet, prevention and early detection are key to limiting outbreaks. This includes reducing bat-to-human contact, improving hygiene around food and farms, and educating communities in high-risk areas.

The WHO has listed the Nipah virus as a priority pathogen requiring accelerated global research, including vaccines and antibody therapies, though widespread availability remains distant.

While the current outbreak in West Bengal appears contained, health authorities and experts urge continued vigilance. Local surveillance, transparent communication and international cooperation remain central to preventing small clusters from becoming larger public health emergencies.

Stay tuned to The World Times for related news.