We all know the standard lists. They’re full of important books you should read like unpayable debts. But the books that truly claim us are rarely the ones we’re assigned. They’re the ones we discover by accident in the silent, dusty stacks of a library, pressed into our hands by a friend with a knowing look, or stumbled upon in some late-night corner of the internet. These are the secret passages into a deeper understanding of literature and of life itself.

In that spirit, this list is a quiet rebellion against the predictable canon. You won’t find your usual suspects here. No Hemingway, no Fitzgerald, no Austen. Instead, these five books span two centuries, four countries (France, Italy, Japan, and the U.S.), and multiple genres. Each one is taught in university courses, yet every pick still surprises even the most seasoned reader.

These books don’t just tell a story; they transform the way you think about stories. They are profound without being pretentious, surprising without being gimmicky, and they are the ones we, as literature students, passionately defend in late-night debates.

1. The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

What It’s About:

Edmond Dantès has it all: a bright future, a loving fiancée, and loyal friends. Then, in a single day, he’s betrayed and thrown into a dungeon for a crime he didn’t commit. His escape and transformation into the mysterious Count of Monte Cristo sets the stage for one of literature’s greatest revenge stories.

Why a Literature Major Picks It:

I hand this book to anyone who claims classics are boring. While my peers were deconstructing Victorian poetry, I was marveling at how Dumas built a narrative engine of pure plot that also asks a devastating question: What happens to the soul when vengeance becomes its only purpose? It’s a page-turner that philosophically punches way above its weight.

The Takeaway:

Proof that a 1,200-page 19th-century novel can be more gripping than anything on today’s television.

“All human wisdom is contained in these two words — Wait and Hope.”

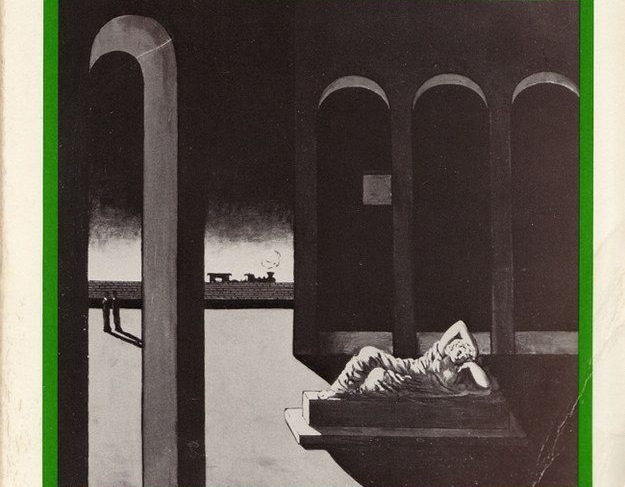

2. If on a winter’s night a traveler by Italo Calvino

What It’s About:

You, yes you, the reader, pick up Calvino’s new novel. But just as you get immersed, the story cuts off. From there, your quest to find the rest of the book leads through ten different, unfinished novels and into the company of another reader, a woman named Ludmilla.

Why a Literature Major Picks It:

This is the book that made me fall in love with literary theory without ever feeling like I was doing homework. Through its clever structure, Calvino turns the reader into a character in his meta-fictional game. It’s a celebration of why we get lost in stories, and it redefined my role from passive consumer to active participant. It’s the most fun I’ve ever had thinking about how reading works.

The Takeaway:

It will change how you think about your role in the story because, in this one, you are the main character.

“You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino’s new novel, If on a winter’s night a traveler.”

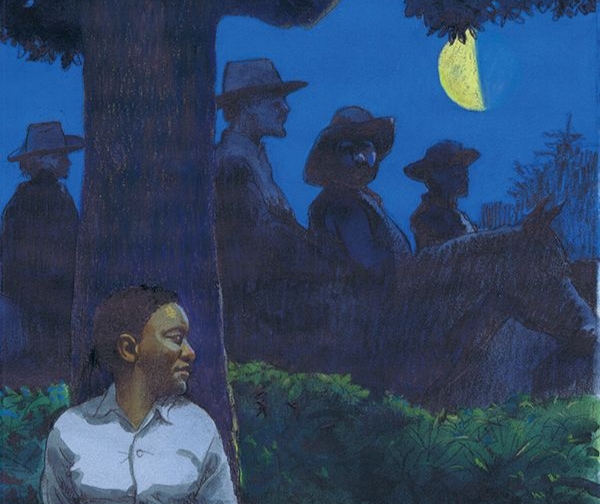

3. Kindred by Octavia E. Butler

What It’s About:

Dana, a Black woman in 1976, is abruptly pulled back in time to the antebellum South to save a drowning white boy who turns out to be her ancestor. To ensure her own existence, she must return again and again, surviving the brutal reality of slavery.

Why a Literature Major Picks It:

Kindred is the book I cite when people dismiss genre fiction. After all, Butler uses sci-fi not to escape reality, but to clamp down on it with terrifying force. She makes the past visceral and inescapable. It’s not just a history lesson; it’s a masterclass in embodied empathy. Ultimately, it reminds us that sometimes the best way to examine our past is through a speculative, deeply personal lens.

The Takeaway:

A novel that uses the future to confront the past, creating one of the most unforgettable explorations of American history ever written.

“I never realized how easily people could be trained to accept slavery.”

4. The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea by Yukio Mishima

What It’s About:

In a Japanese port town, a boy named Noboru idolizes a sailor, seeing him as a symbol of pure, untamed freedom. But when the sailor falls in love with Noboru’s mother and chooses a life on land, admiration curdles into something dark and nihilistic.

Why a Literature Major Picks It:

I read this in one breathless sitting and spent the next week unpacking it. Mishima’s prose is clean and precise, yet carries a violent undertow. At its core, It’s a dark, beautiful puzzle about the idols we build and what happens when they prove human. The ending has stayed with me for years, a perfect, unsettling note that questions everything about love, honor, and decay.

The Takeaway:

Proof that a short book can hit harder than a thousand-page epic. The sharpest stories leave the deepest scars.

“We absolutely must preserve the purity of our dreams.”

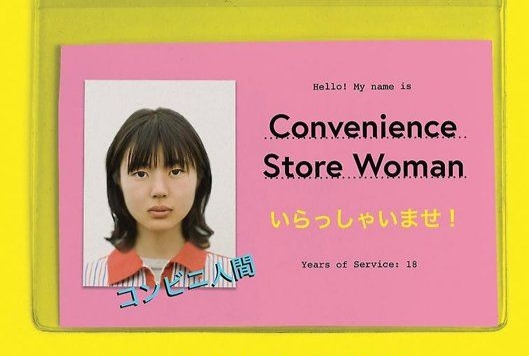

5. Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata

What It’s About:

Keiko has never quite fit in. She finds peace in the routines of her job at a convenience store, until her friends and family pressure her to pursue a “real” life with a career and husband. Her quiet rebellion forces her to ask: what does it really mean to be normal?

Why a Literature Major Picks It:

Keiko is one of the most refreshing, subversive heroines I’ve ever encountered. In many ways, Convenience Store Woman feels like a quiet rebellion against the seminar rooms where we over-intellectualize ‘the other.’ Through Keiko’s beautifully logical voice, Murata exposes the absurdity of the social scripts we all perform. It’s funny, unsettling, and liberating; a defense of choosing your own kind of happiness.

The Takeaway:

Sometimes the most revolutionary act is simply being yourself.

“A person who’s considered normal by society is only someone who’s good at pretending to be normal.”

So there you have it, five testaments to the truth that the right books aren’t just diversions; they’re keys that unlock a new room in your mind. These are the volumes we pass along not to decorate your shelf, but to disrupt your thinking. They’re the quiet arguments in the ongoing conversation about what it means to be human; a conversation that spans centuries, continents, and now, you.

Remember this: classics aren’t the books that everyone has read; they’re the books that have read everyone. So pick one up. Let its first sentence be a door you choose to open. Walk through it. The room on the other side might just be the one where you finally meet yourself.

For more reading that challenges and connects, stay tuned to The World Times.