When mental health influencer Divija Bhasin launched her “Proud Randi” campaign in response to online harassment, she sparked a debate that often arises in contemporary feminism: Who gets to reclaim which slurs, and at what cost to the most marginalised?

Divija Bhasin, The Campaign and Its Fallout

Divija Bhasin, with over half a million Instagram followers, is no stranger to online misogyny. As a prominent mental health advocate with recognition from Harvard and Forbes, she receives gendered abuse daily. Her “Proud Randi” campaign aimed to defang the insult by embracing it, stripping it of its power to wound.

The movement quickly went viral, with supporters praising the bold confrontation of misogyny. But it also raised alarm bells when minors began adding the hashtag to their profiles without understanding its meaning, raising serious questions about online safety and responsibility. More fundamentally, it was argued that Bhasin’s attempt at reclamation represented not empowerment but erasure of the word’s brutal history.

The Caste Dimensions of “Randi”

To understand why this movement proved so controversial, we need to reckon with what “randi” actually means in the Indian context. This isn’t merely a generic slur for women who transgress sexual norms. It names a specific violence rooted in caste.

Women from multiple marginalized communities in India have been forced into intergenerational prostitution for centuries. The Bedia, Perna, Nat, and Banchhada castes were classified as “criminal tribes” under British colonial rule, losing their traditional livelihoods as dancers and performers. Women were pushed into prostitution as a survival strategy that became hereditary.

Among the Perna caste, women face what researchers call “thrice oppression”: born into poverty, into a marginalised caste, and female. Girls typically enter sex work after marriage and childbirth, with families threatening violence if they resist. In Bedia communities, girls are introduced to prostitution as soon as they reach puberty. Their fathers and brothers work as pimps, and entire families survive on the women’s earnings.

The stigma compounds the exploitation. Other castes refuse to allow their children to play with Bedia children, who are taunted as “Bedni ke“. The children often end up leaving school due to constant humiliation. This is social death enacted daily, across generations.

The cultural framework that justifies this exploitation has deep roots. Systems like devadasi marked women from historically marginalized castes as “ritual functionaries who are sexually accessible” to upper-caste men. A Marathi saying captures this brutal logic explicitly: “Devdasi devachi, bayko sarva gavachi”, or “servant of god, but wife of the whole town.”

Divija Bhasin Has Right Intentions, But Also Privilege

This history illuminates why Divija Bhasin’s campaign struck many as tone-deaf rather than transgressive. As critic Sampada Kaul argued, when an upper-caste, educated woman uses the word on Instagram, it doesn’t empower those who’ve actually lived under its weight. Instead, it erases the history behind it.

Kaul made the comparison explicit: she’s been called casteist slurs but doesn’t go around saying she’s “proud” of those words, because reclaiming a slur should come from the community it targets, not outsiders looking in.

The difference in lived experience is stark. Divija Bhasin faces online misogyny, which is real, exhausting, and deserving of pushback. But she doesn’t face the specific intersection of caste-based sexual exploitation that “randi” historically names. She has international degrees, a thriving therapy practice, social media fame, and the ability to choose her career. The women for whom “randi” isn’t an insult but a life sentence have none of these options.

What Intersectional Feminism Demands

Intersectional feminism, as conceived by Kimberlé Crenshaw, requires us to ask whose pain we’re centering in our activism. It demands attention to how different systems of oppression compound and create distinct experiences that can’t be collapsed into a single story of “women’s oppression.”

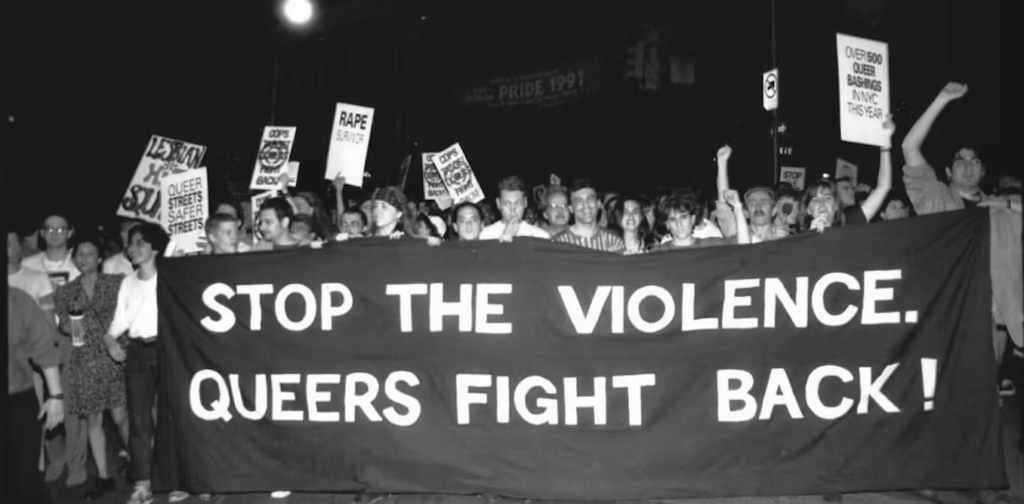

Slur reclamation has a rich history in social movements. Queer communities transformed “queer” from a slur to an identity. Black Americans reclaimed the n-word within their communities. Disabled activists embraced “crip.” But these acts of reclamation share a crucial feature: they come from within the communities that have borne the violence of those words.

The logic of reclamation is that those who’ve suffered under a slur can rob it of power by refusing to be shamed by it, by wearing it as armour. But when someone outside that specific oppression attempts reclamation, the dynamic shifts. It can become a form of appropriation that commodifies trauma for social capital.

Slur Reclamation Can Only Be Empowering In Context

The anger driving the “Proud Randi” campaign is valid. Women are constantly policed and degraded through gendered slurs, and the impulse to throw it back in harassers’ faces is understandable. But intersectional feminism asks us to sit with the discomfort of recognising that not all forms of resistance serve all women equally.

Perhaps the question isn’t whether to resist misogynistic language, but how to do so in ways that don’t inadvertently erase those most vulnerable to its violence. That might mean savarna feminists amplifying sex worker organising rather than centering their own experiences of being called sex workers. It might mean recognising that some slurs aren’t ours to reclaim, even when they’re weaponized against us.

Intersectionality isn’t about ranking oppressions or silencing anyone’s pain. It’s about developing a more sophisticated analysis of how power works, so our resistance doesn’t accidentally reproduce the hierarchies we claim to oppose. In this case, that means reckoning with how caste, class, and the influencer economy shape whose acts of “empowerment” get celebrated and whose survival remains invisible.

Read more on Gender, Culture and Society on The World Times.