An Ode to Joy and a sorrowful succumbing. What follows is a mystifying series of deaths of renowned composers — all in the course of their 9th symphony.

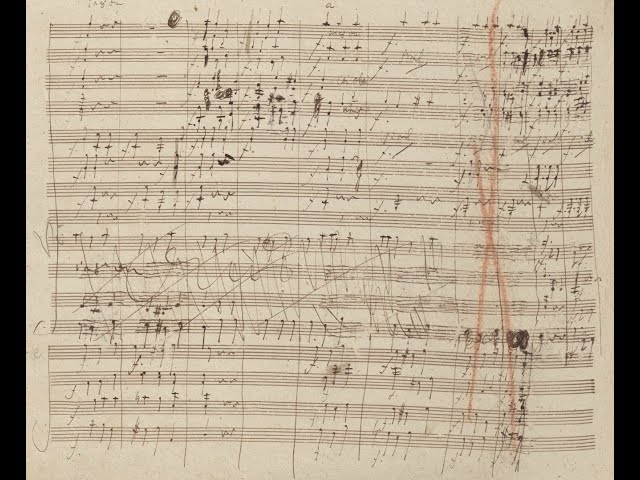

The year is 1824. It has taken Sir Beethoven about 30 years of solitude from public life to compose his final masterful piece, “Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125″. Not only does the symphony harbour the iconic Ode to Joy now used as a symbol of camaraderie between nations, but this work also aids the composer’s autobiographical message to the world, finding light in the darkness.

However, despite his legacy, much of Beethoven’s subsequent mortal endeavours were in vain. Apart from the premiere of his 9th symphony, not much came of him, and he eventually passed away, delivering but a decadent final performance. In this poignant tale of hardship and failure, Beethoven’s death marked the end of a genius foregone, an influencer of the classics, and unbeknownst to many, a trigger of a curse.

The Spark

Franz Schubert (1797-1828), known today for his Leides and the pristine Ave Maria, forged the path to new musical wonders up until the early 19th century. In 1822, he had the honour of meeting both Weber and Beethoven, and that was when the latter recognised his talent. Schubert was a foreseen gift, that is, until his untimely death in 1828 — one year after his idol’s passing. At 31, Schubert was said to have died of typhoid fever, a common consequence of contracting syphilis. This outcome was not, however, before his request to be buried next to Beethoven, for whom he had carried the torch a year prior.

In this tale of master and student, divine and devotee, Beethoven and Schubert’s brief stint is an admired tale loved by historians of the classical realm. This odd but heartwarming episode captured the hearts of many till the curse’s next victim was discovered.

The Flame

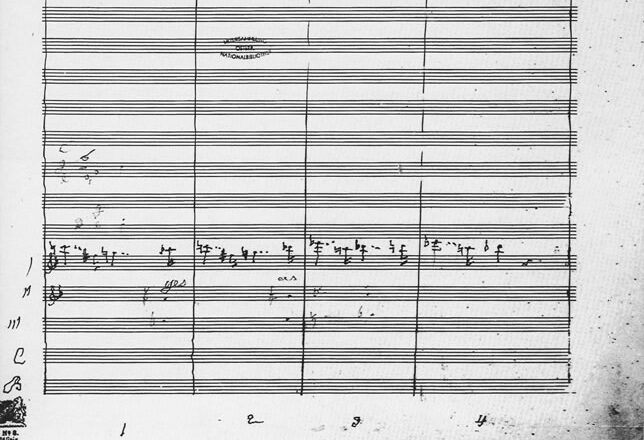

Anthony Bruckner (1824-1896), like Beethoven, was a perfectionist; never content with their work, and always revising their editions. This is what Bruckner was said to be likely doing with his 9th symphony. He was infamously known for his obsessions with death and nervous breakdowns that soon caused him to be diagnosed with numeromania, the historic rendition of OCD. In 1896, at 72 years old, the strange composer succumbed to his death, leaving behind an unfinished symphony and many questions regarding this trend.

However, it was not until Gustav Mahler that the curse was more consciously recognised. Mahler was an incredibly superstitious individual, deeply impacted by the deaths of his forefathers, and went so far as to make attempts to bypass the curse. After he premiered his 8th symphony, Mahler released Das Lied von der Erde, structurally a symphony disguised as a song-cycle. He then went on to write his 9th symphony with ease, thinking that he had beaten the curse. However, as soon as he started working on his 10th symphony, in 1911, pneumonia came, took his life, and materialised the curse.

Another notable victim of the curse was Ralph Vaughan Williams, who, according to a close friend, died mysteriously 3 weeks after the premiere of his 9th symphony in 1958.

The Extinguisher and A Legacy

Many nay-sayers of the curse have come and gone, trying to prove the curse is nothing but a fluff of the classical zeitgeist. Mozart lived to write 41 symphonies at his time, Shostakovich 15, and many others bypassed the “curse of the 9th”. However, what many forget is the initial trigger of the curse — Beethoven’s 9th. Maybe what Schoenberg said was right; maybe “the Ninth is the limit”. Despite these unfounded assumptions, one thing is certain. Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 changed the very nature of how we view the world, each other, and how we approach music. Maybe the curse is not something to be feared, but a comforting reminder to the mortal sufferer of the potential impact they may have centuries later.

Read more such insightful pieces at The World Times.